I Return to the Family

I return to the family, soon to be refugees, travelling in the dark of the year to pay taxes, to be counted in the census, the advanced state of pregnancy of one young mother notwithstanding. I contemplate this family in ceramic and wood, in sculpture and bas-relief—it is Christmas, and the Nativity is everywhere —on table tops, window sills and mantels; it is on people’s lawns glowing against the snow, it is on flags and posters and decals in car windows. It is on television screens. I return to the family—another family (they are also on television screens) looking for shelter—looking for a safe place to give birth on a bitter night of late December, two thousand years later than the family on the decals in the car windows and glowing against the snow outside the Post Office, only tonight, for this family there is no barn, no manger—tonight there is no guiding star—there are bombs and blooming white phosphorous, which does resemble a star but a less holy one, no safety below its arms. In the story of Christ’s birth his family is forced to leave Bethlehem and refugee to Egypt, the lives of all new born sons in peril, seen as they are as a threat to the throne—babies being ever a threat in the Bible. This December the babies being born in the Holy Land, the families that see not stars at night but imminent death have nowhere to flee—they have nowhere to refugee—this is genocide, this is ethnic cleansing and they are expected to neither flee, nor survive—neither father, nor mother, nor child.

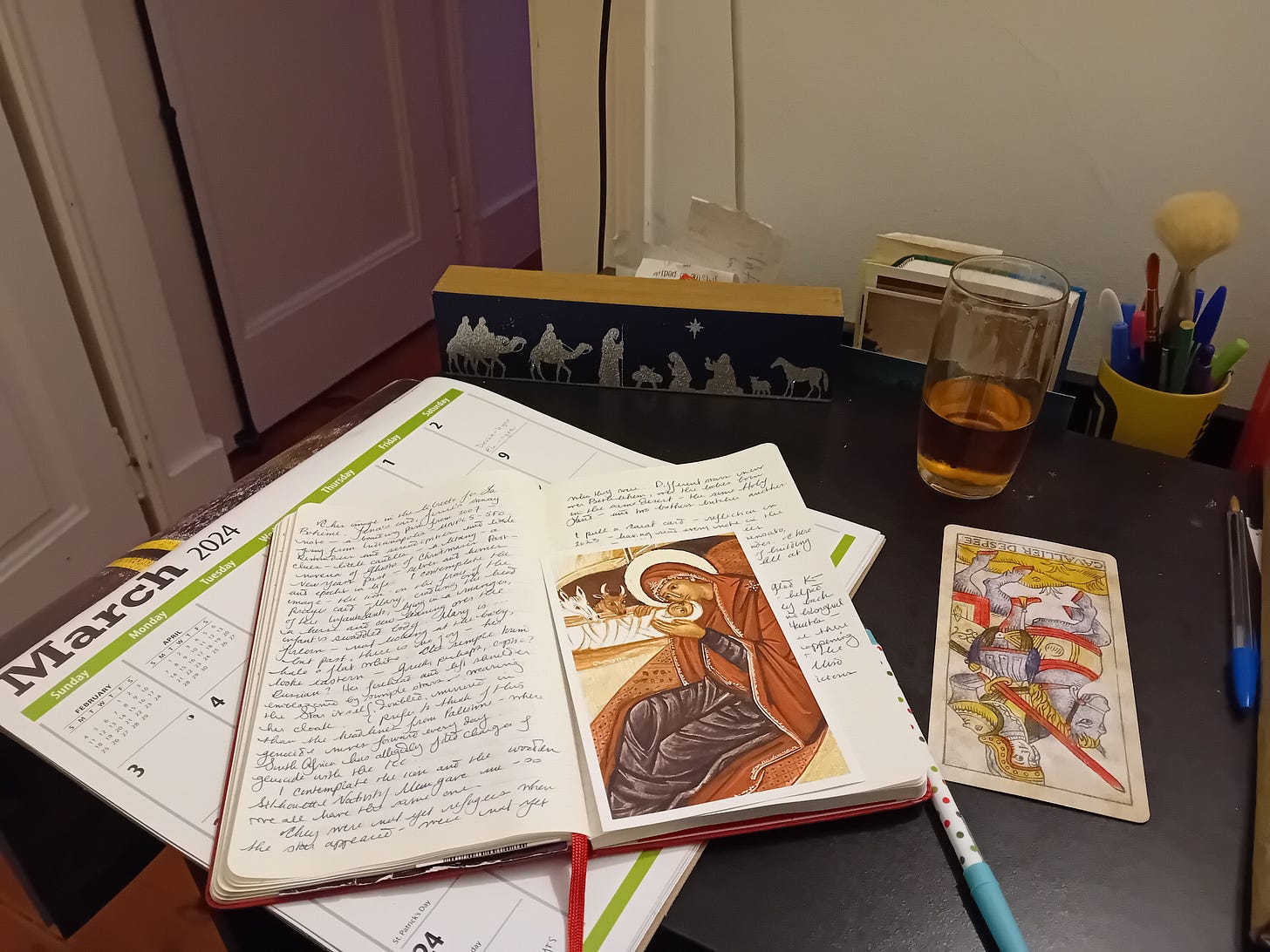

I returned home to Lisbon after spending Christmas on the snowy mirror of the Great Plains with my family. It was our first Christmas together in twenty years, my Christmas returned to my family from the great world beyond, and in every room of my parents’ home, a Nativity, which is not unusual—a Nativity has always been in our home, wherever home was that year, no matter how temporary. It is always up during the whole of Advent, and now my siblings’ homes house the porcelain and ceramic crèches of our childhood—the same ones that my mother and our aunts and uncle set out growing up. This year our mother gifted each of us a simple Nativity, painted onto a lightweight wooden frame, a dark indigo background, the Three Wise Men, the Holy Family, the Star and the requisite donkeys and camels and Shepherd all glitter in silver silhouette. Now we all have the same one, and no matter where we are we’ll be looking at the same Nativity scene, she said to me that night, Christmas. Maybe it was because of the many moves we made growing up, maybe because of the many moves of our mother before us and then with us that we have always had so much devotion to this scene—a family on the move in the winter, seeking shelter, at the mercy of so many forces beyond them and their strength, their lack of power in a world of kings. Every year we contemplate this image—this family—opening the doors of Advent calendars, moving the infant every day closer until the twenty-fourth, the dawning of the Holy Day that follows, the Solstice behind us—the light returning, the birth of the light—the Light of the World, as we are told.

I spent New Year’s Eve jetlagged and contemplating the simple silhouette in indigo and silver, now home on my desk, and a picture of the Madonna and Child, which arrived unexpectedly. This particular Madonna and Child is a prayer card, and it was tucked into the libretto of La Bohème, which I picked up earlier in the day in the book cabinet in the neighborhood garden. The image was unlike any I had previously seen: the Holy Infant is lying in the manger, a cow and horse leaning over him, his mother—the Holy Mother—is leaning over hm too, cradling his head, her gaze looks beyond the frame, forlorn, almost grieving, the eyes of the Infant gazing up at Her—doubtful. I spent the evening looking at the despondent Virgin and the glittering Wise Men, the Shepherd looking worshipful at the Star above and I wondered about blessings and suffer the little children and International Conventions and justice and what is love?

What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life, Mary Oliver asked us? Bare witness, I think as the fireworks announce midnight. Rage against the dying of their lights, I think as the street outside explodes in silvery confetti and horns and the turning of another year. Say their names, I think. Refuse to be drawn into turning away through the lazy manipulations of fear and bigotry and baseness. I have not ever been sure I understood what was meant by integrity, in the truest sense, and less so when it seemed there not much to challenge it in a general one. I did not feel certain I understood what it was to possess integrity, to have it, and less certain of its purpose. I begin to see, now, I think, its beginning—its purpose. Bare witness. Rage against the dying of their light. Say their names.

I return to the family seeking shelter, seeking a place to give birth in late December in the Holy Land. I return to the family—any number of families—who did not survive to see dawn on the twenty-fifth because it was not a guiding star that night but a bomb, a guided bomb and war planes and tanks and civilians as targets—even unto those not yet born, not yet drawn their first breath, enclosed as they are still within their mother’s fragile yet sheltering womb—and across the world our glittering trees, our merry radios and ugly sweater and white elephant parties and our petty family quarrels. I return to the family seeking shelter where ninety percent of the shelters have been reduced to rubble, the homes gone, and with them families—entire families.

I return to the family.

Thought provoking, tender, reminding us of our fortunateness ... luv goodest man luv Catch luv

I am moved by your story of returning to your family after such a long absence, the nativity gifted to you and your siblings, and mostly the realization that some of us live in a world of great, though humble privilege, where so many have so little and lost so much. May our good deeds in our corner of the world, our mitzvah, help to be part of the healing of this very fractured world - tikkun olam.